|

At Lawyers, Guns, and Money, Robert Farley writes:

"The idea of drug legalization runs aground on the shoals of American capitalism. While marijuana has proven too harmless for the pharmaceutical industry to weaponize, the combination of corporate marketing and the political influence of large companies has helped create and extend the extremely destructive “opioid epidemic” that we now find ourselves in. Done carefully (as has generally been the case in Europe) legalization can yield better social outcomes than prohibition, but given extant US political economy it’s as likely as not to yield tremendous human misery. I can think of two caveats off the top; first, any public policy done badly is likely to have bad effects, and so of course drug legalization needs to be approached with care and caution. Second, however awful the opioid epidemic has become, it’s not obviously worse than the prison industrial complex that prohibition has created (although it distributes costs differently). That said, there may be a middle ground between legalization and prohibition that minimizes human misery."

0 Comments

In City Journal, Christopher Caldwell profiles Christophe Guilluy:

“A more important advantage, as geographer Guilluy sees it, is that immigrants living in the urban slums, despite appearances, remain “in the arena.” They are near public transportation, schools, and a real job market that might have hundreds of thousands of vacancies. At a time when rural France is getting more sedentary, the ZUS are the places in France that enjoy the most residential mobility: it’s better in the banlieues. ... For every old-economy banker in an inherited high-ceilinged Second Empire apartment off the Champs-Élysées, there is a new-economy television anchor or high-tech patent attorney living in some exorbitantly remodeled mews house in the Marais. A New Yorker might see these two bourgeoisies as analogous to residents of the Upper East and Upper West Sides. They have arrived through different routes, and they might once have held different political opinions, but they don’t now. Guilluy notes that the conservative presidential candidate Alain Juppé, mayor of Bordeaux, and Gérard Collomb, the Socialist running Lyon, pursue identical policies. ... [Paris] residents have come to describe their politics as “on the left”—a judgment that tomorrow’s historians might dispute. Most often, Parisians mean what Guilluy calls la gauche hashtag, or what we might call the “glass-ceiling Left,” preoccupied with redistribution among, not from, elites: we may have done nothing for the poor, but we did appoint the first disabled lesbian parking commissioner. … The good fortune of Creative Class members appears (to them) to have nothing to do with any kind of capitalist struggle. Never have conditions been more favorable for deluding a class of fortunate people into thinking that they owe their privilege to being nicer, or smarter, or more honest, than everyone else. … Three years after finishing their studies, three-quarters of French university graduates are living on their own; by contrast, three-quarters of their contemporaries without university degrees still live with their parents. And they’re dying early. ... L'Insée announced that life expectancy had fallen for both sexes in France for the first time since World War II, and it’s the native French working class that is likely driving the decline. In fact, the French outsiders are looking a lot like the poor Americans Charles Murray described in Coming Apart, failing not just in income and longevity but also in family formation, mental health, and education. ... French elites have convinced themselves that their social supremacy rests not on their economic might but on their common decency." Wolfgang Streeck tells it like it is:

Almost a century ago, Max Weber drew a distinction between class and status. Classes are constituted by the market; status groups by a particular way of life and a specific claim to social respect. Status groups are home-grown social communities; classes become classes only through organization. The Trumpist electoral machine mobilizes its supporters as a status group. It appeals to their shared sense of honor more than to their material interests. … As the United States was transformed into a polity of status groups, the working class lost its sense of identification with the country as a whole, if only because it is this class, reduced to one identity and interest among others, that is now blamed for a rich variety of social malignancies, from racism and sexism to gun violence and educational and industrial decline. … Globalization favors the equal access of everyone to worldwide markets. It has no use for national citizenship or national citizens. Another moral system is at work. Cultural reeducation is required to erase traditional solidarity and replace it with a morality of equal access and equal opportunity regardless of status (such as “race, creed, and national origin”). … Classes struggling over the correction of markets give way to status groups struggling over access to them. At issue are not the terms of exchange and cooperation between conflicting class interests, or the limits of exploitation of one class by another, but status groups with established market access excluding status groups without it from competition. In the United States, the UK, France, Sweden, and Germany, the old working class, gathered in declining regions and cut off from glimmering global cities, has for some time felt sidelined by what it perceives as a new politics of entitlement by victimhood. … Arlie Hochschild has described the deep divisions between traditional American communities and a hegemonic urban culture declaring it a moral duty for citizens to extend communitarian feelings of compassion, solidarity, and brotherhood from neighbors and friends to everybody, from kind to mankind and indeed humankind. Those unable to comply with the demand for conspicuous compassion are widely regarded as morally defective. … Even if Trump learns how to govern, there is no reason to believe that he will be better than his predecessors at dealing with the crises of global capitalism and the international state system that have brought him to power. Increasing inequality, rising debt, and low growth are not easily cured. Trumpism is, after all, an expression of the crisis, not its solution. ... In the absence of a stable class compromise between capital and labor, policy is doomed to become capricious. …" Also: “Marx described Bonapartism as a popular form of government by personal rule. It arose, he argued, in stalemated European societies, with the capitalist class too divided, and the working class too disorganized, to instruct or inform the government. The result was a degree of relative state autonomy, one expressing, even as it masked, a deadlock between social classes. Bonapartist politics is driven by the idiosyncrasies of its Bonaparte. This is not a recipe for effective rule. Since a capitalist society under Bonapartism lacks the power to control, or contain, market forces, capitalists can afford to let their Bonaparte stage spectacles of political bravado; behind the scenes, markets do what markets do. …" Another bit of interest: "If democracy is understood as the possibility of establishing social obligations toward those luckless in the marketplace, the global elites had entered into, or created, a world in which there was a great deal of lucklessness and not many obligations. … The old left having withdrawn into stateless internationalism, the new right offered the nation-state to fill the ensuing political vacuum. Liberal disgust at Trumpian rhetoric served to justify the withdrawal of the left from its constituents, and to explain its failure to help them express their grievances in civilized public language." Maciej Cegłowski writes:

"The economic basis of the Internet is surveillance. Every interaction with a computing device leaves a data trail, and whole industries exist to consume this data. Unlike dystopian visions from the past, this surveillance is not just being conducted by governments or faceless corporations. Instead, it’s the work of a small number of sympathetic tech companies with likable founders, whose real dream is to build robots and Mars rockets and do cool things that make the world better. Surveillance just pays the bills." And: "A question few are asking is whether the tools of mass surveillance and social control we spent the last decade building could have had anything to do with the debacle of the 2017 election, or whether destroying local journalism and making national journalism so dependent on our platforms was, in retrospect, a good idea. We built the commercial internet by mastering techniques of persuasion and surveillance that we’ve extended to billions of people, including essentially the entire population of the Western democracies. But admitting that this tool of social control might be conducive to authoritarianism is not something we’re ready to face. After all, we're good people. We like freedom. How could we have built tools that subvert it? As Upton Sinclair said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” I contend that there are structural reasons to worry about the role of the tech industry in American political life, and that we have only a brief window of time in which to fix this." Fatih Guvenen and Greg Kaplan, drawing on IRS and SSA data, write (pdf):

"So far in the 21st century (2001–2012): IRS and SSA data reveal diverging patterns in top income shares – the IRS data show a steady increase, whereas the SSA data show no increase at all. The difference is due to the increasing importance of income accruing to pass-through entities (partnerships and S-corporations), which is included in the IRS measure of total income but not in either the IRS or SSA measure of labor income. Moreover, the bulk of this growth in income from pass-through entities was concentrated at the very top of the distribution – above the 99.99th percentile, a group that contains only about 12,000 households. The share of incomes above the 99th percentile (around $372,000 in 2012) but below the 99.99th percentile (around $7.2 million in 2012) has barely changed in the last two decades." Diane Coyle on UBI, in the FT:

"Once in a generation, an automation scare triggers a bout of enthusiasm for a universal basic income — a payment made to all citizens regardless of work, wealth or their social contribution. Today’s discussion of the merits of UBI echoes similar debates in the 1960s and 1990s. But the appeal of this palliative for the replacement of humans by machines is misplaced. The starting point for thinking about how a government should respond to an intense wave of creative destruction in the economy is an acknowledgment that previous policy responses have failed. Governments did not have anything to offer in response to the deindustrialisation (thanks to automation) of large areas, and the loss of millions of jobs. People found that their governments had breached the implicit social contract of the postwar welfare state. ... But it is hard to see why [UBI] would do better at addressing the economic and social costs of large-scale redundancy than the previous policy of making payments to those who lost their jobs. The problem is a hole torn in the fabric of a local or regional economy and society; giving people money is a temporary patch. ... One advocate of a version of a guaranteed income was Milton Friedman, who supported it in part because of its focus on the individual. This is exactly why it would be an inadequate response to a significant economic shock. No individual can deal with a major technological change in the structure of the economy." On police bias in Florida Highway Patrol speeding tickets, Tim Taylor reports:

"There is an enormous spike in those given tickets for being about 9 mph over the speed limit. ... In Florida, the fine for being 10 mph over the limit is substantially higher. ... the spike at 9 mph is higher for whites than for blacks and Hispanics. This suggests the likelihood that whites are more likely to catch a break from an officer and get the 9 mph ticket." "Bias and discrimination doesn't always involve doing something negative. In the modern United States, my [Taylor's] suspicion is that some of the most prevalent and hardest-to-spot biases just involve not cutting someone an equal break, or not being quite as willing to offer an opportunity that would otherwise have been offered." And: "[T]he majority of officers exhibit no bias, with the aggregate disparity in treatment explained by the behavior of a small minority of officers composing about 20% of the patrol force. We also explore how bias varies with officer-level characteristics, documenting that officers exhibit own-race preferences and that younger, female, and college-educated officers are less likely to be biased." Link to the paper by Goncalves and Mello here. Interview with Charles Koch on Nautilus:

[Q:] We also know Neanderthals had bigger brains than the Homo sapiens who lived near them in Europe. Yet we survived and they didn’t. [A:] Their brain was maybe 10 percent larger than our brain. We don’t know why we survived. Did we just outbreed them? Were we more aggressive? There’s some research showing that dogs play a role here. At the same time when Homo neanderthalensis became extinct—around 35,000 years ago--Homo sapiens domesticated the wolf and they became the two apex hunters. Homo sapiens and wolves/dogs started to collaborate. We became this ultra-efficient hunting cooperative because we now had the ability to be much more efficient at hunting down prey over long distances and exhausting them. So the creature with the larger brain didn’t survive and the one with the smaller brain did. The New York Fed's blog reports on job search:

"The most surprising finding is that search is common among employed workers. ... roughly one in five or one in four employed workers actively looked for work during the four weeks preceding the survey." The average number of applications sent in the last four weeks was 4.6 for employed workers actively looking for work, and 8 for the unemployed. Elizabeth Kolbert writes "Republicans now control 33 state legislatures, just one shy of the number needed to circumvent Congress and call a constitutional convention." Pseudoerasmus summarizes Sven Beckert’s Empire of Cotton. Alan Háyek in Aeon: heuristics for philosophy. Terry Gross interviews Adam Cohen about American eugenics and ties to the progressive movement, Wendel Holmes’ despicable ruling, and the science-y underpinnings of 1927 immigration law that fixed immigrant quotas to 1890s levels. Michael Haneke, in an interview with Paris Review:

"I despise films that have a political agenda. Their intent is always to manipulate, to convince the viewer of their respective ideologies. Ideologies, however, are artistically uninteresting. I always say that if something can be reduced to one clear concept, it is artistically dead. If a single concept captures something, then everything has already been resolved—or so it appears, at least. Maybe that’s why I find it so hard to write synopses. I just cannot do it. If I were able to summarize a film in three sentences, I wouldn’t need to make it. Then I’d be a journalist … I’ve never seen good results from people trying to speak about things they don’t know firsthand. They will talk about Afghanistan, about children in Africa, but in the end they only know what they’ve seen on TV or read in the newspaper. And yet they pretend—even to themselves—that they know what they’re saying. But that’s bullshit. I’m quite convinced that I don’t know anything except for what is going on around me, what I can see and perceive every day, and what I have experienced in my life so far … We, in our protected little worlds, are much more numb because we are in luck not to experience danger on a daily basis. But that’s precisely why the film industry in the so-called first world is in such a rut. There is just so much recycling. We don’t have the capability to represent authentic experiences because there is so little we do experience. … I’ve seen it many times in my circle of friends—that when someone is caring for a sick partner, they will just fall apart. Not the one who’s sick, but the partner who is taking care of him. If that goes on for months or years even, those people end up hardly recognizable. People who care for a loved one get crushed under an immense burden. … whether it’s a good or a bad film depends entirely on its form. Everything is a story. The Holocaust is as much a story as is the tale of Rumpelstiltskin. Now the real question is, what do you do with it? What will you make of your story and how are you going to tell it? That alone determines how it will be received. A naked woman is a naked woman, but Velázquez’s naked woman is different from Picasso’s naked woman. The form determines the artwork and distinguishes it from the work of a dilettante. … I’m always keen to stress that music is the queen of the arts because in music, form and content are identical." Third Way covers work by Jerry Davis. From the intro:

"“For the past 20 years, public corporations in the United States have been disappearing. The number of U.S.-based companies listed on Nasdaq and the New York Stock Exchange has dropped by over half since 1996.” And while the dot.com bust and the financial crisis had something to do with this, the trends have continued. “The number of new entrants,” Davis writes, “does not come close to matching the exits.” ... Davis looks at the kinds of companies that have exited the stock market. The simple answer, over-regulation, cannot explain the decline. The more fundamental explanation is that there has been a change in the kind of businesses we are creating today; they have more access to other forms of capital, firms no longer need to build assets because they can rent them, and thus, “Scaling up and scaling down, are much simpler than they were in the heyday of the traditional corporation.” Davis concludes that “the public corporation was an ideal vehicle for the 20th-century economy, characterized by long-lived assets and economies of scale. But it is increasingly out of sync with the 21st-century economy.” The disappearance of the corporation, however, is not without consequences. “The firms that have gone public since 2000 rarely create employment at a large scale; the median firm to IPO after 2000 created just 51 jobs globally.” “In 2015,” Davis writes, “the combined workforces of Facebook, Yelp, Zynga, LinkedIn, Zillow, Tableau, Zulily and Box were smaller than the number of people who lost their jobs when Circuit City was liquidated in 2009.” Moreover, the old-fashioned corporation served a social purpose. It was the source of long career ladders and stability, of health care and retirement savings for millions. Davis doesn’t think the old corporation is coming back, which poses a big question for policymakers-- how do we promote economic security and mobility in a post-corporate economy?" Nate Cohn at the Upshot compares official voter files to The Upshot’s pre-election turnout projections:

"Large numbers of white, working-class voters shifted from the Democrats to Mr. Trump. Over all, almost one in four of President Obama’s 2012 white working-class supporters defected from the Democrats in 2016 ... On average, white and Hispanic turnout was 4 percent higher than we expected, while black turnout was 1 percent lower than expected. ... The increase in white turnout was broad, including among young voters, Democrats, Republicans, unaffiliated voters, urban, rural, and the likeliest supporters of Mrs. Clinton and Mr. Trump. The greatest increases were among young and unaffiliated white voters. ... If turnout played only a modest role in Mr. Trump’s victory, then the big driver of his gains was persuasion: He flipped millions of white working-class Obama supporters to his side." VoxEU covers the new Piketty, Saez & Zucman paper. Tidbits:

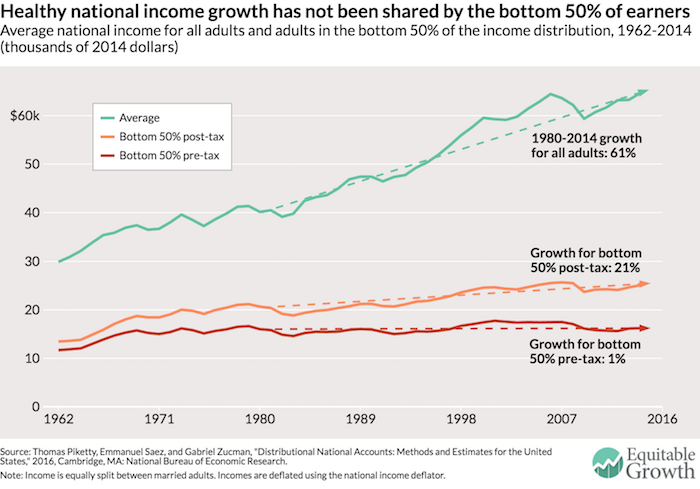

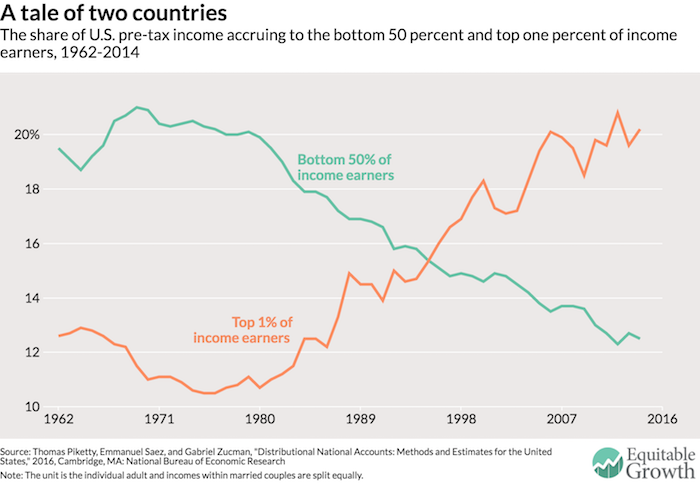

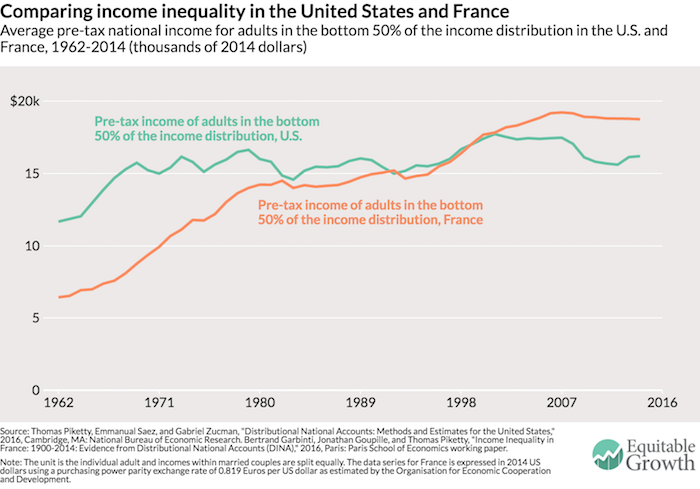

"The total flow of income reported by households in survey or tax data adds up to barely 60% of the national income recorded in the national accounts, with this gap increasing over the past several decades. [Footnote 1: Many important forms of income, such as fringe benefits of employees, retained profits and taxes paid by corporations, or imputed rent of homeowners, are part of U.S. national income but are not included in individual survey or tax data.] ... An economy that fails to deliver growth for half of its people for an entire generation is bound to generate discontent with the status quo and a rejection of establishment politics. ... To understand how unequal the US is today, consider the following fact. In 1980, adults in the top 1% earned on average 27 times more than bottom 50% of adults. Today they earn 81 times more. This ratio of 1 to 81 is similar to the gap between the average income in the US and the average income in the world’s poorest countries, among them the war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, and Burundi. Another alarming trend evident in this data is that the increase in income concentration at the top in the US over the past 15 years is due to a boom in capital income. It looks like the working rich who drove the upsurge in income concentration in the 1980s and 1990s are either retiring to live off their capital income or passing their fortunes onto heirs." |

AboutThis is my notepad. Archives

January 2018

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed